What will happen to Philippine businesses?

Nel owns an internet shop in Metro Manila. She has 10 computers in her garage which she rents out to gamers from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. Her customers pay a peso for every four minutes or P15/hour for games. Nel says she can earb P1,300-P1,500 a day or P20,000 to P25,000/month, after subtracting payment for electricity which can reach P12,000 and the P3,000 internet fee.

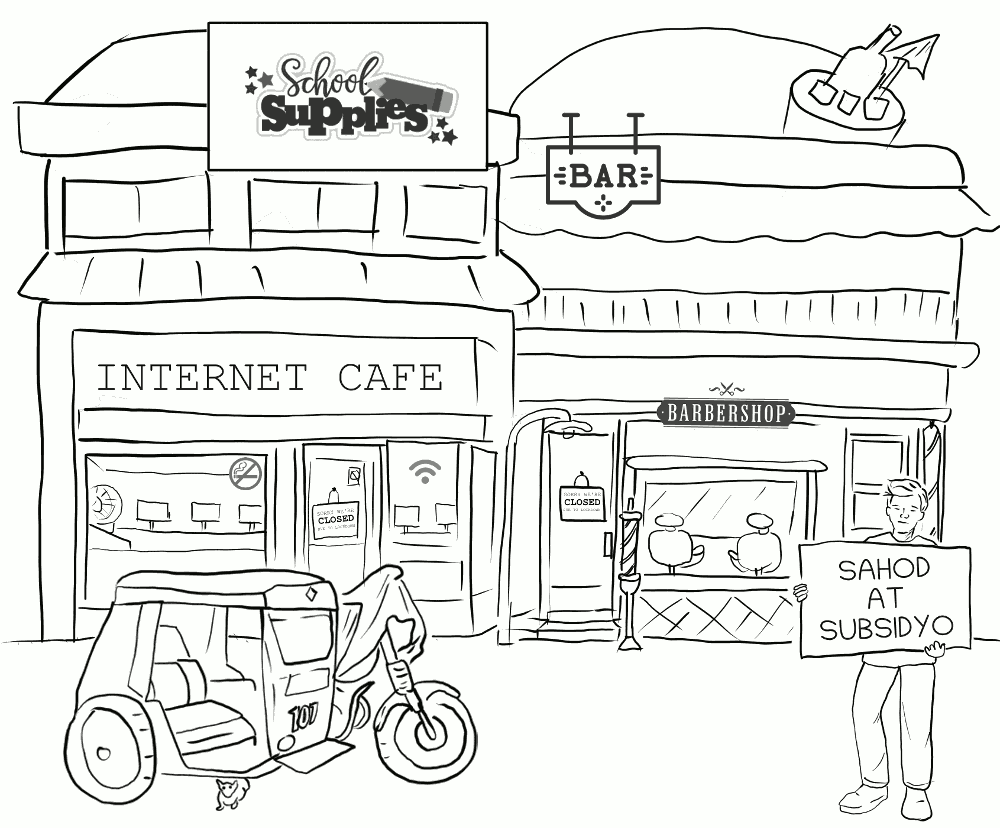

When the lockdown was imposed, she was forced to close shop as gaming stations were deemed not essential. She lost her income as she relied on what gamers pay her everyday. But even as she stopped operations, she still had to pay her electricity and internet bills. Her meager savings were soon depleted as she provided for her family’s daily needs. As she was not categorized as one of the “poorest of the poor,” she was not included in the regime’s list of food and financial aid beneficiaries.

Like Nel’s shop, hundreds of thousands of stores, eateries, parlors, barbers and other small businesses closed shop during the lockdown. Thousands of professionals like consultants, lawyers, musicians and other self-employed lost their income. Small hotels and resorts, eateries and restaurants catering to local and foreign tourists were ordered closed.

According to the reactionary state’s data, there are 998,342 small and medium enterprisess in the Philippines in 2018. These comprise 99.5% of all establishments in the country. A great majority of these (90%) are micro or enterprises which has nine workers or less and up to P3 million in capital. Almost half of these micro enterprises (427,101) are in wholesale and retail; repair of vehicles and motorcycles,as well as all personal and household items. Next biggest is in the accomodation/food-related subsector (125,396); and third in the manufacturing subsector (103,590). Most small manufacturers are in the food business, such as bakeries. These businesses are wholely- or majority-owned by Filipinos. These are oftentimes managed and operated by families. Most affected are businesses in Luzon which make up two-thirds of the total number of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises, and which employs 3.8 million.

The Duterte regime issued aid for small businesses but in the form of loans. The Department of Trade and Industry is giving out loans from P200,000 to P500,000 but only registered businesses are qualified. Enterpreneurs estimate that this will only cover rent, electric and water utilities, payment to unpaid debts incurred during the lockdown, and to suppliers for materials spoilt due to the lockdown.

During the 2-month lockdown, small and medium enterprises have used up their emergency funds to pay their workers. The regime’s promise of P5,000 to P8,000 wage subsidy was too little and late. On April, only 120,000 applications were approved by the Department of Labor and Employment. The agency terminated its subsidy when it ran out of funds.

Across the nation, 2.7 million workers stand to lose their jobs. This include 11.5 million self-employed or those who own their businesses, 5.7 million in the informal sector and 10.1 million non-regular wage and salary earners.

Government agencies estimate that around 436,000 businesses were force to shutdown by the lockdown. Only 117,000 big and small essential businesses were allowed to operate.

To avoid closures, the state needs to pour P79 billion subsidy per month for small and medium-sized businesss. This includes P53.5 billion compensation for 10.7 million workers and P26 billion for businesses in the informal sector. Price control for basic commodities is needed. Payments for loans, rent and utilities should be deferred. The chain of supply should be ensured. Agricultural products need to be bought in a timely manner and at reasonable prices. Loans should be with zero interests. Most significantly, steps should be taken to ensure the health of all returning workers, especially as the Covid-19 threat lingers.