The Marcos borrowing binge, a recurring historic phenomenon

Third part of the series on the Duterte regime’s borrowing binge. Read the first part, “Pandemic borrowing binge,” in Ang Bayan, August 21, 2020; second part, “Predicament to be caused by Duterte’s borrowing spree,” Ang Bayan, September 7, 2020.

This coming September 21, the Filipino people will mark the 48th anniversary of the declaration of martial law by late dictator Ferdinand Marcos. This was the start of an era marked by innumerable atrocities, cronyism and rampant corruption by the ruling Marcos clique. It was also an era of unprecedented accumulation of foreign debt. After more than 14 years of martial rule, Marcos left the country in ruins and heavily in debt.

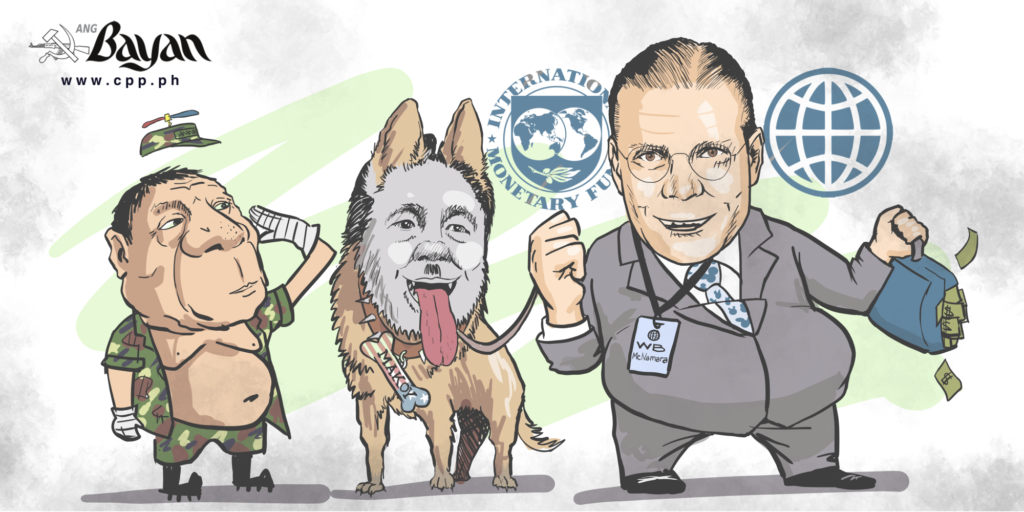

Much like Duterte today, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos colluded with imperialist financial institutions to fund his grandiose infrastructure program purportedly to spur economic growth in the country. Marcos borrowed heavily from the US-controlled International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (WB) to fund 61 of these projects. These included the notorious Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP) in Morong, Bataan, and many other projects that turned out to be white elephants and provided Marcos and his cronies huge kickbacks.

The IMF-WB were all too willing to lend the US-Marcos dictatorship with massive amounts of dollars. Since the start of the 1970s and through the 1980s, the US imperialists pushed for debt-driven “sustainable development” to unload the imperialists of their surplus dollars.

Upon declaring martial law, Marcos liberalized borrowing and made policy adjustments in compliance with IMF-WB conditionalities. He immediately removed the ceiling on public borrowing dismantling the debt margin which was initially pegged at $1 billion with an annual ceiling of just $250 million.

By allowing unlimited borrowing, Marcos accumulated $2.6 billion in loans from the WB alone in 1973-1981, nearly eight times bigger than what the country received between 1950 to 1972. By 1980, the Philippines became the WB’s 8th top recipient of loans among 113 poor countries. Simultaneously, loans from foreign private banks also ballooned from just $2 billion in 1972 to $24.5 billion in 1983. All in all, Philippine foreign debt, including state-guaranteed private debt (so-called “behest loans”) skyrocketed from just $600 million (current value at ₱30 billion) in 1965 to more than $26 billion in 1986 (₱1.3 trillion).

The borrowing binge was managed by former Prime Minister Cesar Enrique Virata, a WB-trained technocrat, who concurrently served as Finance Minister and head of the dictatorial regime’s National Economic and Development Authority. In turn, the IMF-WB openly supported the dictatorship, clearly symbolized by its annual general meeting in 1976 which was held in Manila.

By 1980, the Philippines became the top recipient in Asia and 2nd in the world for structural adjustment loans (SALs). These loans came with conditionalities including tariff cuts, removal of import licenses and quantitative restrictions, additional taxes, privatization of public assets, deregulation, labor-export, wage cuts and many other anti-people and market-oriented reforms. These neoliberal measures will later be come to be known as the Washington Consensus.

The SALs incurred from 1980 to 1984 totaling to more than $500 million were accompanied by policy conditions which mark the beginning of decades of Philippine neoliberal restructuring. Among others, average tariff protection was significantly cut from 43% in 1981 to just 28% in 1985 resulting in bankruptcies among local enterprises leading to massive job losses. By 1985, the unemployment rate reached 12.6% from just 3.9% in 1975. Prices of basic goods and services also dramatically increased as the inflation rate soared to nearly 30% in 1985 from 6.8% in 1975.

Contrary to attempts at historical revisionism which conjure the illusion of “golden years” under the US-Marcos dictatorship, the economy actually collapsed during martial law under IMF and WB promises of development.

Despite the nominal restoration of democracy after the dictator was ousted in 1986, all succeeding regimes, including the incumbent Duterte regime continue to uphold and implement IMF-WB-imposed neoliberal reforms. This has been a constant with all post-Marcos regimes, as the country continue to grapple with chronic budget and trade deficits borne out of its export-oriented, import-dependent economy.

Starkest among these reforms is the policy for automatic debt servicing which was implemented by Marcos through Presidential Decree 1177 in 1977. Speaking before the US Congress after rising to the presidency at the heels of the EDSA uprising, Corazon Aquino, notoriously promised that the Philippines will pay all of Marcos’ debt. She later issued the Administrative Code of 1987 to institutionalize automatic debt servicing. Over the past decades, the Philippines has appropriated from 20 to 45% of the national budget to service its foreign debt and has assiduously implemented neoliberal policy measures. In the 1980s, this was to earn the so-called “seal of good housekeeping” of the IMF. These days, this is to get positive reviews by imperialist credit-rating agencies and earn the triple-A rating of “credit worthiness” in order to borrow more money.

Duterte’s corrupt-ridden infrastructure program and insatiable appetite for massive borrowing brings back memories of the dark period of crisis under the Marcos dictatorship. In this aspect, as in all aspects of tyranny, the people are correct in saying “never again” to unbridled public borrowing.