by Ricardo Lozano Life of a revolutionary compatriot

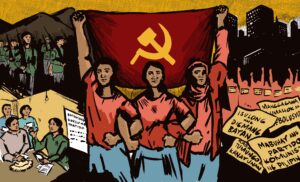

The struggle of Filipino migrants, despite being away from their homeland, remain rooted in the Philippine struggle for national and social liberation. Cognizant of the semi-feudal and semi-colonial conditions back home that forced them to work abroad, Filipino migrants can be organized as a formidable force of the revolution.

Statistics from the International Labour Organization (ILO) suggest there are over 10 million Filipinos living abroad globally. This is on top of thousands of Filipinos who have immigrated abroad, those who remain undocumented as well as refugees in various parts of the world. These comprise the Filipino diaspora, tied by their common stories of sacrifice, hope, and revolution. As they navigate the complexities of adjusting to a different life abroad subjected to intense exploitation and oppression, they recognize that their freedom can only be won by taking part in the national democratic struggle for liberation.

We interviewed members of Compatriots, the revolutionary organization of Filipino migrants and their families, and an allied organization of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), to find out more about their daily struggles, the challenges they face in organizing compatriot masses and what it’s like to live as a revolutionary compatriot.

Fertile ground for organizing

Filipino migrants are exposed to various forms of exploitation, oppression, racism, and discrimination. This common thread that ties compatriots together make the ground fertile to organize them in their millions for the national democratic revolution.

“As class conscious revolutionary forces, we organize migrants by first making them understand and realize how they are exploited and capitalized upon both by big businesses through wage depression, and the Philippine government by raking in billions from their remittances only to pay off international debt,” tells Jenny, a part-time migrant worker and revolutionary migrant organizer.

“We can also organize them by helping them with their immediate needs. In many cases, we are able to organize migrants who are rescued from situations of abuse or other forms of modern-day slavery,” Jenny adds. According to some estimates, around 49.6 million people live in conditions of modern slavery – in forced labor and forced marriage situations majority of whom are migrant women.

“The moment they understand their situation and the moment they realize that the only way to change things is by taking part in the struggle for national democratic revolution, Filipino migrants can become a strong core of revolutionary strength,” explains Jenny. Organized Filipino migrants play a key role in shaping international public opinion in support of the Philippine revolution. In their thousands, they can either pressure political actors abroad to take action on human rights violations committed by the Philippine government, or also generate substantial moral and material support for the revolution.

Filipino migrants abroad can come from various class origins – from peasants who are forced to sell their land and eventually sell their labor power in another country, petibourgeois professionals who are underpaid for their work in the Philippines, or workers who risk everything for a better life in a foreign land – these make up the wide range of forces that can be organized for the liberation of Philippine society.

Challenges faced by revolutionary compatriots

But “organizing work among Filipino compatriots isn’t always easy,” says Dina, also a member of Compatriots and works as a household cleaner in Europe. “Organizing work among migrants, like in other sectors, is also fraught with challenges much of which has to do with the very limited time they can spare to be with us in meetings or participate in educational discussions and other activities,” admits Dina. Most Filipino migrants, especially undocumented migrants, take on two or three jobs jumping to clean from one household to babysit in another according to Dina.

Dina wakes up early and begins her day navigating the intricate web of odd jobs that sustain her livelihood and her family back home. With a worn-out backpack slung over her shoulder, she moves from one house to another, always on the lookout for a day’s wage. Calloused from countless tasks, Dina’s hands tell the tale of labor and sacrifice. Despite her busy schedule, she still finds time to do mass work and organize among the ranks of Filipino migrant workers.

“Many of the masses we have organized have proven that it is possible to participate in political actions despite balancing time for economic work. The moment they see the organization alive and functioning, they become inspired to be part of it and give more time for political action,” Dina explains.

“Individualist tendencies tend to exacerbate especially for migrant workers here in advanced capitalist countries,” says Dina. She argues that the work available for migrant workers are mostly in the service industry or so-called “black jobs” that often rely greatly on the individual efforts and hardships – from cleaning houses, babysitting, waitressing, and other house-based chores.

“This becomes a challenge for migrant organizers in terms of developing their social consciousness and a collective way of life,” adds Dina. “Nevertheless, we are able to overcome these challenges through pain-staking ideological work. By giving out educational discussions to raise their consciousness and allow them to break through the individualist mindset with which they have been trained for a long time,” she explains.

“As a revolutionary compatriot, you must also be always on guard against your own individualist tendencies – to situate yourself as a revolutionary, and not a mere Kababayan. This means you must be able to apply revolutionary ideas to the current situation faced by migrant workers abroad and organize them for the cause of revolution in the homeland,” said Dina.

Life full of sacrifices

“The life of a revolutionary compatriot is a life full of sacrifices. Imagine having all the opportunity to earn more money so you can send more back to your family at home but giving that up so that you can spend more time doing political work,” said Jenny.

Jenny recalls how she would sometimes have to give up a gig just to respond to urgent migrant concerns; how despite not knowing how to replace the lost income, she takes comfort in knowing the masses will support her and provide for her needs. “Despite being away from the Philippines, the spirit of Bayanihan prevails among our Filipino compatriots. Whenever someone needs a place to stay, some food to eat, or even just company, our migrants are always ready to help out,” she adds.

Jenny wakes up at five in the morning to prepare for her first job as a part-time warehouse staffer. She leaves work around 12 noon for a quick break and travel to the next village to clean a household or two where she earns 15 euros per hour of cleaning. She spends the remaining part of her day to meet up with other Filipino migrants to hold educational discussions or participate in political actions. In her free time and especially during weekends, she would spend most of her day in social gatherings of traditional migrant organizations to expand her network for organizing.

“It was difficult at first to adjust to living abroad, away from family. I had to learn a new language, adjust to a new culture, and jump from one job to another just to survive,” explains Jenny. “It was also challenging to find the right balance between economic work to earn just enough for me and my family back home to survive and find enough time to do the work I set out to do – which is to organize other migrants for the Filipino revolution,” she added.

“But these are sacrifices that I’m willing and prepared to take. Situating oneself in the Filipino revolution is possible despite being thousands of miles away from the civil war at home,” Jenny said.

Indeed, the life of a revolutionary compatriot is not a walk in the park. It requires constant self-remolding in the face of bourgeois influences especially in advanced capitalist countries where the temptation to “bourgeoisify” is strongest. But amid the constant uncertainty and relentless hardships, our revolutionary compatriots find solace in the camaraderie of their fellow migrant workers whom they arouse, organize and mobilize. Their day unfolds as an inspiring illustration of simple living and arduous struggle.