Low poverty standards, a lever to push down wages

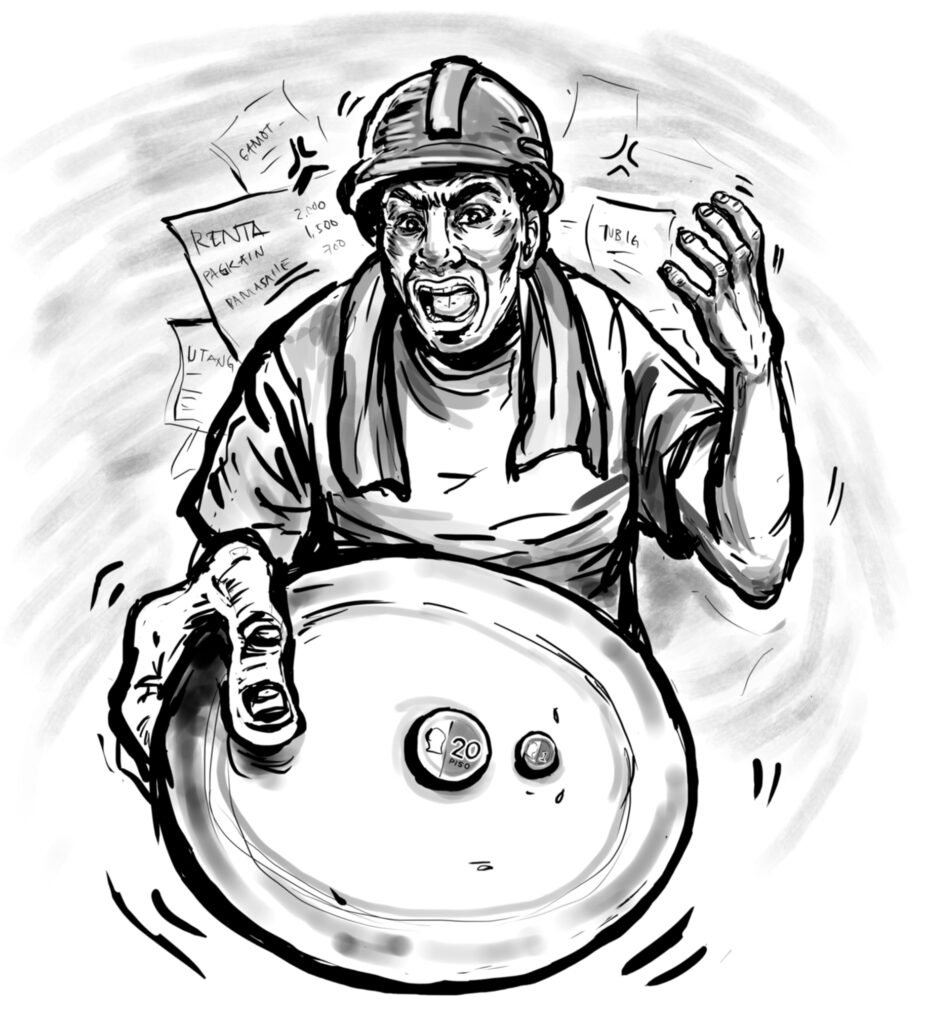

The Marcos regime drew left and right criticism when its officials defended the ₱21/meal or ₱64/day as measure of hunger and ₱91/day as the standard of poverty. Using this, Marcos claims that a 5-person family spending ₱9,581/month is no longer “food poor.” Making false prices and rates, the current regime made boasts that the number of impoverished Filipinos has “declined” from 18.1% in 2021 to 15.5% in 2023.

To lower hunger standards, the Marcos government changed the contents of the “subsistence food basket” of food items necessary for survival. For example, it categorized noodles as a viand and mongo with anchovies as protein source, instead of fish or meat, which were removed from the list. Not content with reducing the basket contents, it invented prices such as ₱7/package for noodles instead of ₱11/pack and ₱4 for 3-in-1 coffee instead of ₱8 from retailers.

Marcos officials falsely reduced “non-food” expenses such as housing, water, electricity, fares, medical services and other basic necessities. This is far from the truth being barely sufficient for an ordinary family’s electricity bill alone. As of June, a family consuming only 200kwh/month already paid ₱1,890.32 (₱60/day or ₱12/person). The remaining ₱15 is not enough for the minimum return fare.

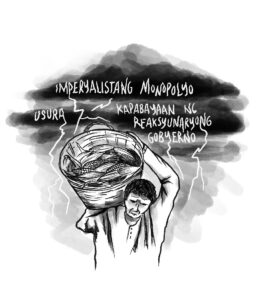

Other than its goal of conjuring an improving condition for the people, this statistical manipulation is a way to further pull down or prevent the increase in wages and salaries of workers and employees. This rationale is being used to prevent significant increases in the minimum wage, which is also used as grounds to prevent wage increases for skilled workers. Because of this, the standard of living of the masses of workers, farmers, staff and ordinary citizens continuously plummets.

In 2023, the state set the national poverty threshold at only ₱13,873/month or ₱462.43/day. This is only half of Ibon Foundation’s estimate of ₱26,210/month or ₱873.66 per day (equivalent to ₱1,207 daily wages for a 5-day work week). The Marcos regime uses such very low poverty standards to justify measly wage increases of ₱35/day in 2023 and ₱40/day this 2024.

Even worse is the two-tier wage system adopted since 2012 and first implemented in Southern Tagalog. The first tier is set below the minimum wage or the average wage of workers in the region, which further drags down workers’ wages. The second tier, which is supposedly based on productivity, is only set at the capitalist’s whims, and still needs to be negotiated.

Living wages against poverty

Ibon’s studies show it is more realistic to look at the number of Filipino families living below the living wage to show the true face of poverty. It said about 13.7 million families live on ₱23,000/month or less. Meanwhile, the 19.2 million who live on ₱29,000/month or less can be considered to be at the poverty line.

Calculations by Ibon show that a family of five needs at least ₱26,261/month to live decently. Most of this will be spent for food (₱13,740), followed by housing (₱4,666), electricity, water, LPG, others (₱2,722), other services (₱1,788) and transportation (₱1,487). The rest (₱1,851) will be divided for household goods, communication, health expenses, clothing, education, special occasions, alcohol, entertainment, savings and others.

In a study by the Ateneo Policy Center last August, a family needs at least ₱693/day (₱20,790 per month or ₱138.66/person) for food alone. This is to meet the dietary requirement set in the “Pinggang Pinoy” (Filipino plate), a standard released by the state’s Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI). Using the cheapest ingredients, the study found that a healthy diet costs at least ₱46.20/meal in the National Capital Region, while it costs ₱43.80/meal in other parts of the country.