In retrospect: Youth's struggle for democratic rights during martial law

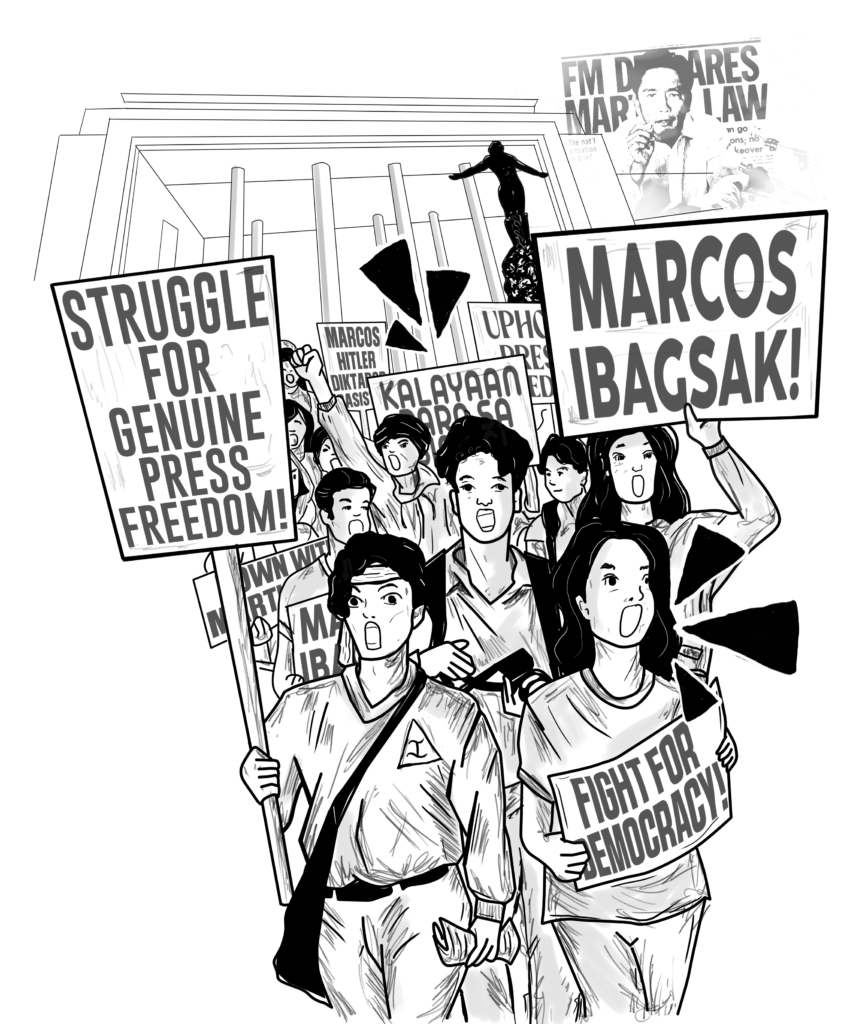

When the US-Marcos dictatorship imposed martial law in September 1972, the regime outrightly banned student councils, organizations, fraternities and publications in universities and schools. This is part of the overall suppression of the democratic rights of the youth and the entire people.

Marcos considered all groups of students and youth a threat to his military rule. He sent scores of agents to universities to pose as students, teachers or employees to spy on and identify those critical of his regime.

The dictatorship openly controlled the administrations of the universities. It also repeatedly attempted to break the emerging unity of the youth through brutal arrests, intimidation and the militarization of universities.

Despite these, the spirit of resistance of the youth and students remained undefeated. They worked hard to raise awareness, organize and mobilize fellow youth for their democratic rights.

They first challenged the dictatorship with silent marches, flash protests, petitioning, leaflet circulation, posters and graffiti calls and other creative means to raise the awareness of the broad masses regarding the situation under the regime. Publications on campus also served as a medium for calls to action and struggle of students and the Filipino masses. Eventually, these would give rise to a massive protest movement.

Rally of 200,000 young students

Five years after the declaration of martial law, the Marcos dictatorship was shook by large rallies of young students asserting their democratic rights. This led to a massive rally in July 1977 where nearly 200,000 students from 10 colleges and universities joined. They boycotted their classes at the University of the Philippines, Araneta University Foundation, University of the East, Adamson University, Trinity College, Philippine College of Commerce, University of Santo Tomas, Philippine Women’s University, Feati University and Philippine College of Criminology.

They rallied under the Student Alliance Against Tuition Fee Increases. It asserted seven main demands, including the removal of all troops and agents of the reactionary Armed Forces of the Philippines from the campuses; reinstatement of student councils under martial law; and a stop to tuition fee increases.

The extent of the action forced the Marcos dictatorship to stop the plan to raise the tuition fee of private schools for the following semester. This inspired the youth movement to further strengthen its efforts to push the Marcos dictatorship to recognize their democratic rights. In the following year, various universities gradually achieved the return of student councils and the revival of campus newspapers.

Unrelenting struggle

Several decades after Marcos Sr’s ouster, it is important to hold on to the democratic rights won by the student movements during martial law. This includes actively establishing councils and operating campus newspapers. This becomes even more important amid continuous imperialist cultural and ideological offensives which promotes individualism and liberalism to disunite and divide young students and take away their power as a social and historical force.

Students have long used their councils and campus newspaper as source of strength and voice against oppressive campus administrations. This is especially crucial presently amid the need to thwart the attacks of the Marcos regime, particularly the National Task Force (NTF)-Elcac, and the restoration of military and police agents and forces on campuses.

“Students and these institutions must protect and support each other,” a campus journalist quipped.