Production further slumps, unemployment balloons

Mass layoffs and factory closures marked the Philippine economy in 2023. Tens of thousands of jobs were lost en masse as foreign companies moved their operations overseas. The most striking examples are the mass layoffs in Mactan Export Processing Zone, including 10,000 layoffs from Sports Center International, a Taiwanese company, which supplies clothing to large American and European companies. There were also layoffs at semiconductor companies, such as Nexperia, a Dutch company, which closed a department to save on production costs and target the local labor union.

According to a study by Ibon Foundation, up to 1.4 million people lost their jobs in November 2023. This is a third of the total employment in the manufacturing subsector in November 2022. Currently, 2.9 million are employed in the subsector, almost just as many as in 2003 (2.8 million). Current manufacturing employment numbers are at a 20-year low.

The first three quarters of 2023 saw the lowest growth rate of the manufacturing sector in the last 75 years. During that period, the sector was only 17.6% of the total gross domestic product (GDP) in 2023, the lowest level since the 16.3% recorded in 1949. (In 2000, manufacturing was 25% of GDP; and 20% in 2013.)

Manufacturing “grew” by only 0.3% even in the last quarter of 2023, despite capitalists’ hopes that the subsector would be “stimulated”. Manufacturing is expected to plunge steadily in the first quarter of 2024, driven by a typical post-holiday consumption slowdown, high inflation and high loan interest rates. The same is expected for the whole of 2024 due to high prices of basic commodities, raw materials and production costs.

No basic industries

From the outset, foreign capital, mainly of the US, overpowered and stunted emerging industries in the Philippines in the early part of the 20th century. Researches say the growth of Filipino industries has been stunted since the 1960s. This has kept Philippine production backward, agrarian and non-industrialized.

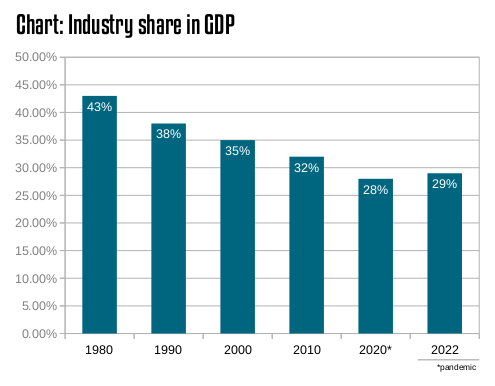

Declarations of the reactionary state that the Philippines will “industrialize” in the first decade of the 2000 century, such as the US-Ramos regime’s “Philippines 2000” slogan, are all hollow and deceptions. Successive regimes implemented all-out neoliberal measures (liberalization, deregulation and privatization) in accordance with the framework of imperialist “globalization” purportedly to “develop” the Philippines. The reverese happened with industry slipping down steadily in over three decades. (See chart). Its share in total employment also did not rise above 15%.

The largest part of manufacturing, in terms of value, is focused on semiprocessing products (assembly and manual inspection) for export. This is part of an international assembly line, in the so-called “global value chain” of monopoly capitalists. Hectares upon hectares of land of labor enclaves (export processing zones or EPZs) were specifically set aside for them where they enjoy benefits and incentives. Recently, they also received further favors with the law exempting them from tax (CREATE law) and policies that provide “ease of doing business.”

Foreign companies in these enclaves are not connected, upstream or downstream, with the local economy, other than employing cheap and docile labor power and skills of Filipino workers. Foreign capitalists take advantage of slave-like wages (especially since the implementation of wage regionalization in 1997) and laws allowing contractualization. They take full advantage of the no-union and no strike policy in the name of “industrial peace,” and in recent years, the NTF-Elcac-led armed repression by fascist military and police.

Foreign capitalists are not obligated to keep or revolve their superprofits within the Philippines. They are also free to move their operations in and out of the country without transferring knowledge or technology that can be used by Filipino capitalists.

In the past four decades, many large companies entered the country, took advantage of cheap labor, benefited from incentives, made hundreds of millions of dollars, but eventually left to move their operations to other underdeveloped countries. Examples of these are companies like Intel Corporation, which operated for 35 years in the country, Hanjin (12 years) and Shell/Chevron (21 years). Then, as now, these companies brought no industrial development, and left leaving nothing but thousands of unemployed workers.