Southern Tagalog remembers the dark years of martial law

Filom (not his real name) was not even 10 years old when he witnessed his grandfather being beaten up by elements of the Philippine Constabulary (PC) in their farm in Barangay Panaytayan, Mansalay, Oriental Mindoro. The reason? His grandfather was carrying a long bolo.

“Things were so strict that even carrying a bolo to town was banned,” Filo, a Mangyan said, as he recalled the abuses of martial law in Southern Tagalog. “A Mangyan, however, cannot be separated from his bolo!”

In addition, Filom and his fellow Mangyans remember PC elements preventing him and others from going to their farms on suspicion that they might be meet up with members of the New People’s Army (NPA).

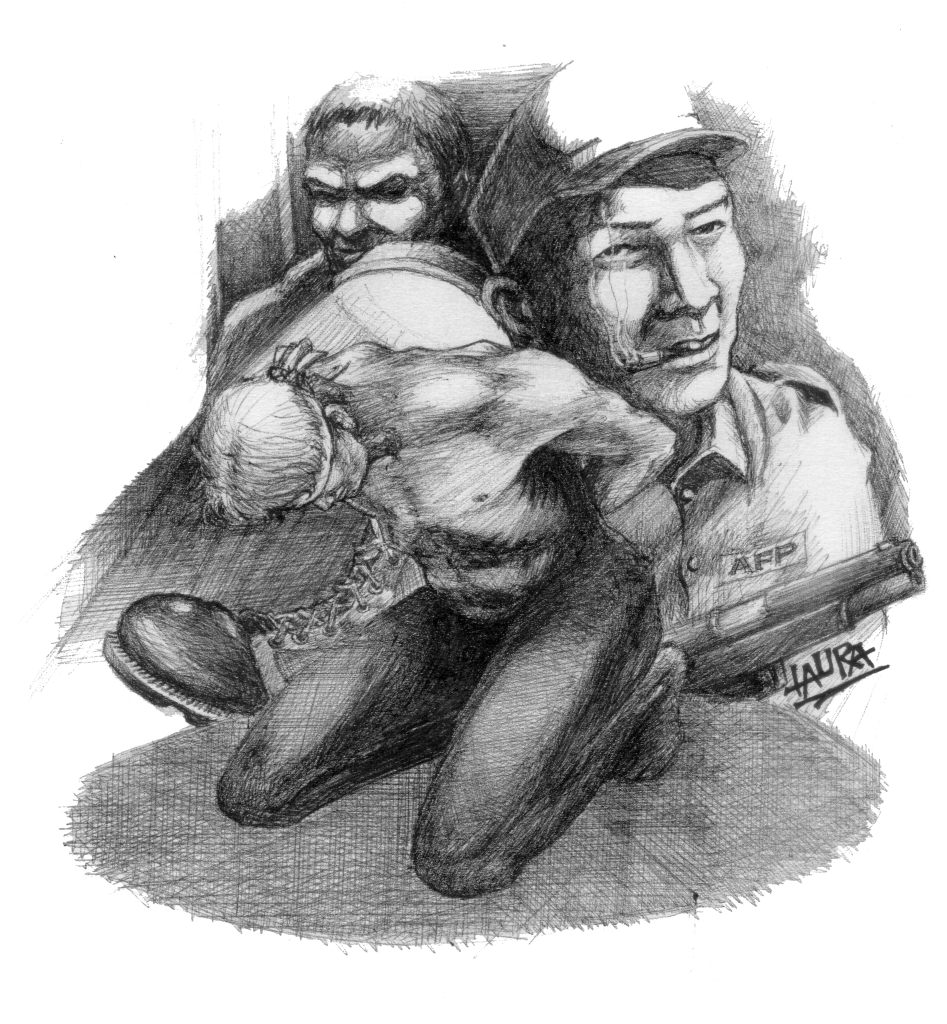

In their village, members of the Mangyan-Hanunuo tribe, accused of having links to the NPA, were tortured and severely abused. Two of the victims were Aloy* and Nomes*, who were Amas or elders and leaders of their tribes. They recalled how PC elements not only harassed the Mangyan people, but also disrespected and trampled on their culture and beliefs. Military operations rampaged through the mountains and blasphemed their sacred places. PC elements dug up graves of indigenous people and scattered the bones of their ancestors in their hunt for “hidden guns of the NPA.”

Around the same period, seven Philippine Army battalions, two PC battalions and a marine battalion landing team were deployed at the boundary of Southern Quezon and Bicol. Each battalion had air support and were supported by Philippine Army Light Armory in their search and destroy operations. Homer, a farmer, recounts how PC soldiers controlled the amount of food purchases. They are also required everyone to sign a logbook every time they tended to their farms.

Areas with suspected NPA units were targets of brigade-sized military operations, supported with aerial strafing and bombings. In April 1974, 800-900 military troops occupied Barangay San Antonio, Kalayaan, Laguna and nearby areas for a month.

Insufficient indemnification

As a victim of martial law cruelty, Tatay (father) Andy received ₱75,000 as indemnification based on the Hawaii Court’s decision against the Marcoses. But this did not ease his pain. In their community in Barangay Quipot, San Juan, Batangas, only four were indemnified although their entire village suffered the cruelty and barbarity of martial law.

In the 1980s, Tatay Andy was accused of having links with the NPA. He was abducted at his house and tortured by the fascists in a camp in Barangay Castillo, San Juan. He was made to lie down with a wet towel on his face as soapy water was poured over his head.

Residents from Barangay Quipot were made to report to the military camp. They were tortured under interrogation in which they were made to crawl on their knees around the camp while others were buried up to their necks. The PC also carried out dastardly acts to drive a wedge between neighbors and families and pitting fathers against their and sons. They would force the son to punch his father strung up by rope. If the son refuses, they would beat him up.

Residents of Quipot were even more vexxed when after the lifting of martial law, the bastards involved in the violence and tortures were promoted.

According to Filom, “it is infuriating that another Marcos now sits as the president of the country, especially since the dictator’s family has not expressed regrets nor acknowledged the crimes of their family especially during martial law.”

The entire nation’s struggle to indict and hold the Marcos family and their factotums accountable for their crimes against the people continues. This is a great challenge as a Marcos not sits in Malacañang and amid systematic revisions and distortion of history to misrepresent the tragic phase of the nation’s history as “golden years.”

“The experience of how people suffered under martial law should be remembered, especially by the youth. Our experiences will serve as a reminder and challenge so that the dark years of martial law will never be repeated,” Tatay Andy said.”